The year…is 1933. March, New York City. A film premiers that would change the face of cinema forever, and inspire hordes of contributors to the history of movie magic. Giants like Ray Harryhausen and Stan Winston were able to run because of the work Willis O’Brien and his crew put in for King Kong. A masterpiece in stop-motion animation and puppetry, Kong broke ground in the giant monster genre to become an instant classic.

As part of the film’s promotion and release in Japan, Torajiro Saito produced a short film Wasei Kingu Kongu, a three-reel comedy that uses footage from the American King Kong as a backdrop, now lost to the annals of time. Years later, America would similarly cut footage from the Japanese film Godzilla interspersed with scenes featuring American actors. This symbiosis would continue heavily as international film industries matured: Japan producing Samurai classics that inspired American-style Westerns in Italy, that in turn inspired more Samurai films, that in turn gave Quinten Tarantino wet dreams.

Godzilla (Gojira in Japan) opened in 1954, nine years after the dropping of the Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. More relevantly, mere months after an incident where the crew of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon 5) were irradiated with fallout from the U.S. Castle Bravo nuclear test at Bikini Atoll in March. Inspired by the success of expensive monster films in the US, and having another project collapse led producer Tomoyuki Tanaka to take on this expensive monster flick in Japan’s resurging post-war film industry. It was a gamble that paid off.

The creature suit itself was a formidable undertaking; with Tsuburaya’s team on a deadline, they could not a create a stop-motion creature, and birthed the “suitmation” style that would come to define the genre. The first suit was so heavy and hot that actor Haruo Nakajima could only operate inside it for three minutes at a time before losing consciousness. Its skin was designed to embody the keloid scars on the victims of radiation poisoning. Most of the footage of Godzilla attacking Japan is shot at night, basking the creature in shadow and emphasizing the horror of radioactive fallout made flesh.

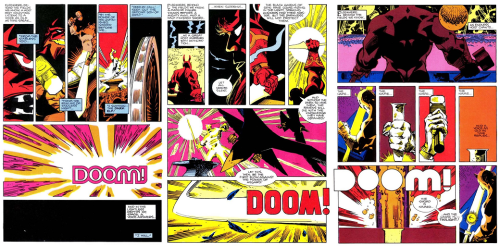

This initial installment is unique in its gravity. Tanaka recruited director Ishiro Honda, a veteran of the war who took the horrors of destruction seriously, and special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya to bring the spectre of nuclear annihilation to life. The film opens with an echoing BOOM…BOOM…BOOM… of gigantic ominous footsteps, leading to the tell-tale roar of Godzilla, reminiscent of a steel beam being rent in half. It sets the dark, somber tone for the film to come as opening credits roll to the now iconic musical theme from Akira Ifukube. The music conveys escalating chaos amid the rhythmic unescapable approach of the giant beast. Incidentally, I can’t help but draw comparison’s to Walter Simonson’s Thor run as each issue steadily hammers out a DOOM…DOOM… while Surtur is forging the Twilight Sword over a series of 9 issues.

The story is given time to breathe after two ships are attacked at sea. The inhabitants of Odo Island mourn for their lost comrades, and hold a ritual to ward off a legendary creature, Gojira, from the superstitious tales of old. We see them gathered ashore, looking for survivors, and you get a real sense of community. When a monsoon hits, and Godzilla attacks the village, the survivors are displaced and petition the government for redress en masse.

We are introduced to Professor Yamane who posits that Godzilla is an ancient dinosaur, mutated by radiation. His daughter Emiko, arranged to be married to a family friend Dr. Serizawa, and the man she loves, Hideto Ogata, a ship captain. Once the stage is set, 1954’s Godzilla is rife with metaphor. Yamane wants to study the beast, and stricken with grief at the idea of killing the last of its kind. His hubris is at odds with the rampant devastation and loss of life all around him. Dr. Serizawa represents the flip side of the coin, and has created a device called the “Oxygen Destroyer,” which has the ability to destroy all life in a body of water. He is overwhelmed with the weight of creating such a destructive invention, and tries to hide it from the world until a good use can be found for it. In the wake of the film’s climactic rampage, Serizawa resolves himself to using the Oxygen Destroyer against Godzilla, but only on the condition that his notes be destroyed — and him with them. He says it must be used only once, and after the world knows of its existence, the knowledge would still be in his own head even after burning the research. Gravely, he admits that he is only human and may someday succumb to the inevitable coercion and torture from world leaders. The Pandora’s Box of the Atomic and Hydrogen bombs, and by extension Godzilla, cannot be closed, and he will not add to this escalating arms race.

The main human story follows Emiko and Ogata as they struggle to consider how to break news of their love to the betrothed Serizawa and Emiko’s father, the professor. It’s touching and fills its narrative purpose, but the real heart of Godzilla lies in its depictions of everyday people. A fishing village distraught and concerned for the lives lost at sea, and later the destruction of their entire homes. Completely displaced, they petition the government for relief. A woman on a train says “I barely escaped the atomic bomb in Nagasaki, and now this?!?” This comment would be edited out of the American version. During a hearing on the attacks, a group of women and reporters demand the world hear the truth, while men from the government want to preserve fragile diplomatic relations. It is an emotional call for accountability. A woman during the attack on Tokyo holds two children close to her, trying her best to comfort them in the face of imminent death: “We’re going to join Daddy! We’ll be where Daddy is soon!” A reporter who has posted up on a tower broadcasts his final moments as Godzilla approaches: “No time to run, farewell ladies and gentlemen!” Surviving children of the carnage are read with a Geiger Counter, which crackles forebodingly. Your heart breaks for these children born into such a violent and cruel world.

In the end, Serizawa sacrifices himself at the bottom of the ocean to kill Godzilla with the Oxygen Destroyer. Professor Yamane laments that Godzilla was the last of its kind, but warns that another will appear if we keep testing nuclear weapons. The message in 1954’s Godzilla is presented in no uncertain terms. This is a cathartic scream of grief from the only nation ravaged by nuclear warfare. The human race is staring down the barrel of a gun, and if we don’t change our ways, this nightmare will be the end of us.

Make no mistake: although this movie is about a giant dinosaur that breathes radioactive fire, it is a solid film. There are moments where it falls into distinctly campy 50s sci-fi exposition mode, but this lays the groundwork for a deeper, more believable story to come. Once you accept the suspension of disbelief, you can be overcome by the legitimate feelings of horror, anguish, dread, and helplessness in the face of the danger that radioactive fallout poses to the world.